It’s Larger Us’s 5th birthday this month. I’d planned to write an upbeat post celebrating what we’ve achieved. But upbeat is the last thing I feel right now.

Larger Us was born in East Jerusalem, about 100 metres from the 1967 ‘Green Line’ between the two sides. We lived there in 2018, when my wife’s work took us there.

I was on sabbatical, frazzled after a year of working on Brexit. I loved being there – it’s an extraordinary, magical place – but God, it was tense.

We’d see homes round the corner from us where Palestinian families were being evicted to make way for settlers.

Down in Gaza, protestors were trying to breach the fence. The word in the diplomatic community was that the IDF snipers were aiming for people’s knees. To maim for life.

One night, we were awakened by deafening rocket alarms on our phones, and raced in panic to get the kids to the safe room before we’d even really woken up.

Another time we were on the tram when all the police and soldiers on board started unholstering their weapons as news emerged of an attack further up the line. My son still gets freaked out by guns.

Psychology and politics

In the middle of all this I met an extraordinary woman called Gina Ross. An expert on trauma and conflict, Gina is unusual in being a Jewish American-Israeli who grew up in Syria – something that gives her deep insight into both sides’ perspectives.

The key thing you need to understand about Israel and Palestine, Gina observed to me when we spoke, is that everyone has Continuous Traumatic Stress (CTS).

If you’re Palestinian, you worry you’ll disappear into indefinite detenion without trial, or your kid will be shot on the way to school by the IDF, or that your house will be the next to be demolished.

If you’re Israeli, you worry you’ll be blown to pieces on the bus, or suffer life-changing injuries in a rocket attack, or that your country will be overrun by hostile neighbours – as nearly happened in ’73.

So you live with constant low-level fear, anxiety, and hyper-vigilance.

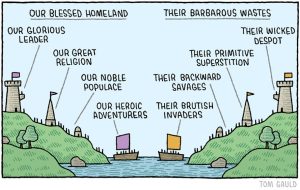

Of course it affects your mental health. But it also provides the perfect soil for ‘othering’ – when you see another group not just as different, but also as inferior or threatening.

And I became fascinated by whether it might be possible to use psychology to do the opposite – to bridge divides, build common purpose, and bring people together. It’s the same question that’s still at the heart of Larger Us’s work.

Five years on

Now it’s five years later, and I’m watching videos of people in the streets of London celebrating attacks in which kids and babies were massacred, or posting memes like the one below.

Meanwhile, I’m reading that Israel’s defence minister has justified cutting Gaza off from food, water, fuel and medical supplies by explaining that Israel is fighting “human animals”.

In each case, it feels like the kind of dehumanisation of the other side that often precedes a genocide.

I feel exhausted. It just seems like a bottomless pit of agony, violence and recrimination that only ever grows. Above all, I feel viscerally how everyone is just looking for safety, and no-one is finding it anywhere.

Jews live with the still fresh memory of a well-organised attempt to kill all of them – an existential trauma that continues to cause mental ill health in the children and grandchildren of survivors. Imagine being one of them and seeing *this* happen in the land that was supposed to provide safe haven. Or seeing so many different people turning out to support Palestinians – but only your own people turning out to support you, even after babies were murdered. How would you feel?

Palestinians live with the still fresh memory of being dispossessed of land they’d lived on for hundreds of years – holding keys to houses they owned before 1948 and may never see again. Imagine being one of them and seeing that dispossession continue to this day, with your kids growing up under the injustice and oppression of an occupation that feels like it will never end – and now with neighbouring Arab countries poised to normalise relations with Israel, uncaring about your plight. How would you feel?

And I have to wonder – have we learned anything over the last five years of Larger Us that’s of any use in a situation like this?

And then I think – yes. Yes, we have.

Not ideas we came up with, for the most part, but ideas we’ve found and thought were valuable. Ideas that aren’t just relevant to politicians, or just to Israelis and Palestinians, but to all of us.

These are a few of them.

10 ideas to help make sense of what’s happening

1. Fight-flight-freeze is everyone’s enemy. Our automatic threat response is great for physical danger, but terrible for political events. We get overwhelmed. Less empathetic. Worse at critical or imaginative thinking. More aggressive. Locked into our in-groups.

2. If it bleeds, it leads. So many players in our information environment have motive and opportunity to keep us in fight-flight-freeze. Populist politicians. Terrorists. Conspiracy theorists. Social media or news media companies wanting to monetise our attention.

3. Mutual radicalisation. When fight-flight-freeze makes us contemptuous or threatening towards the other side, it makes them feel threatened, leading them to be contemptuous or threatening – and so the cycle self-amplifies. Extremists of all stripes love this logic.

4. In-group bias. It’s hard-wired into all of us: whenever we see ourselves as part of a group, we view it more favourably. That’s fine in lots of contexts, but tends to be disastrous where anything political is concerned, because it only gives us…

5. …half the picture. My social media is full of people taking a them-and-us view of what’s happening. Most of them think their side is the victim and the other side is the perpetrator. All of them are correct… as far as their analysis goes. But I’m not sure any of them is helping to transform the situation.

6. Shared loss forms group identity. When societies experience deep shared loss, it can easily become central to group identity. That then leaves them wide open to manipulation by divisive leaders. Look at Putin or Trump. Look at Hamas or Israel’s far right.

7. Recognise the trauma dynamic. Trauma is what happens when fight-flight-freeze gets stuck. It undermines our sense of safety, it hinders us from regulating our emotions, it can be collective and intergenerational, and it can lead us to act out our pain on someone else. Nowhere is all of this clearer than in the Middle East.

8. This will continue until enough people say enough. Trauma not transformed is trauma transferred, as Tabitha Mpamira-Kaguri puts it. Gershon Baskin, an Israeli peacemaker who’s negotiated with Hamas, says what gives him hope is the possibility of a ‘Belfast moment’:

“The moment when we all – the Israeli people and the Palestinian people – wake up and say no more. We don’t want to kill each other any more. We’re tired of dying. We want to sit down together and learn to live together. This is not relevant to our governments, because our governments are wrong and bad and need to be replaced. Our government and the Palestinian government. This needs to come from the people, and maybe after this trauma and this disaster and the death and the horror and the destruction, maybe enough Israelis and enough Palestinians will stand up and say enough. Enough. Enough.”

9. We’re all part of this. This is not just about politicians or people in the region. All of us are involved – in our conversations, on our social media platforms, in how we show up as citizens. We all help open up – or close down – the political space for things to change.

10. If you’re only pro-Israeli or pro-Palestinian, you’re part of the problem. If you’re taking one side or the other, then by definition you are not a peacemaker. The people we need right now are pro-children, pro-civilians, pro-peace – and organising and protesting for that.

10 ways you can be part of the solution

1. Steady yourself. If you’re stuck in fight-flight-freeze, then you’re not helping. It’s natural to feel grief, anger and fear. But we need to process that as healthily as we can and then do our best to come to steadiness. With practice, we can build our ability to make conscious choices about how to respond to things we find threatening. Here’s how.

2. Curate your media diet. When we make intentional choices about the sources and stories we use to make sense of the world, it has both personal and political impact. Do your best to avoid doomscrolling. Try to get out of your echo chamber and find thoughtful voices who challenge you.

3. Change your perspective. Perspective taking – being able to see a situation through someone else’s eyes, and empathise with what they’re thinking and feeling – is fundamental if you want to help build peace (on this, or anything else). This is a good place to start.

4. Listen before you speak. All of us reach for the megaphone when we feel passionate. But as Amanda Ripley says, “humans need to be heard before they will listen”. This is her guide to how to listen to people you disagree with.

5. Ask open-ended questions. Having ‘curious conversations’, where both sides are open to an encounter in which they change their mind about the other, is a profoundly hopeful act. It’s one that can drive deep political change, too.

6. Call in, don’t call out. As great as it feels to shame people for things they’ve said or shared, it usually makes them dig in to their positions (which may well be unconscious or performative). We’ll usually find we can change more if we call them in rather than out. Take a breath – then do it privately, gently, and respectfully.

7. Tell different stories… The stories we use to make sense of crises can easily become self-fulfilling prophecies when we believe them and behave accordingly: think of a bank run. There’s deep power in moral imagination that creates different stories of different futures.

8. …especially of ‘us’. Refusing the extremists’ call to see the world as a them-and-us and instead telling stories of a larger us – where ‘us’ is defined by what we share, not who’s excluded – can have big effects. Look at the Radical Love campaign in Istanbul in 2019.

9. Organise. People power will be vital for a ‘Belfast moment’, but it has to focus on the right aims. ‘Pro-Israeli’ or ‘pro-Palestinian’ protests change nothing. Instead we need protests against the dynamic that holds both sides captive, the extremists who profit from it, and the foreign governments that perpetuate it by supporting one side and not the other.

And we need to be the change we want to see in the world. How we live out our values matters as much as what those values are.

10. What if there were no them? People sometimes ask – aren’t there some people who are always beyond the pale, outside the scope of even the largest us? I guess I have three thoughts on this.

First, the path to healing always runs through truth and accountability. That’s a clear lesson from South Africa and Rwanda, or from restorative justice.

Second, I don’t think anyone is irredeemable. That’s part of my faith as a Christian, but it’s also an empirical position when I look at people like Daryl Davis, the African American who’s persuaded over 200 KKK members to leave. All of us can change.

And third, I always come back to the great author and civil rights activist James Baldwin, and his letter to his nephew in which he writes of white supremacists that,

“…these men are your brothers, your lost younger brothers, and if the word ‘integration’ means anything, this is what it means, that we with love shall force our brothers to see themselves as they are, to cease fleeing from reality and begin to change it, for this is your home, my friend.”